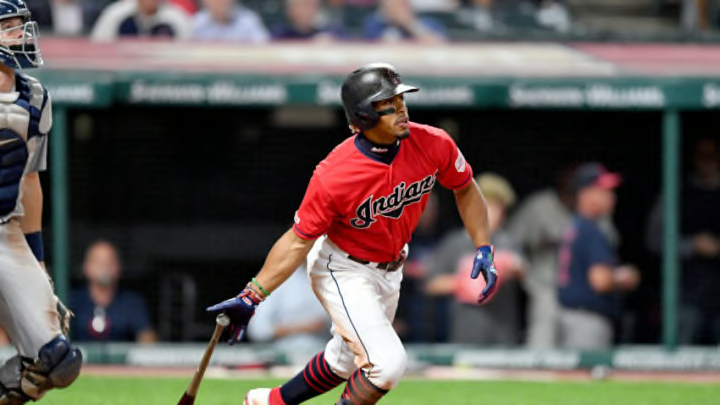

How hard should the Indians work to keep Francisco Lindor? The fact we are even asking the question is a bad sign the Cleveland Indians

The right move for the Indians with Francisco Lindor depends on how you measure the success of a team. Does keeping Lindor help the Cleveland Indians win? To an extent, yes. He is one of the top five players in all of baseball, and young enough that he would be likely to maintain an elite level of performance for at least another decade. He has no character of injury issues that would raise a red flag. With no salary cap in baseball, signing Lindor would not obligate the Indians to skimp in other areas to pay his salary; but they would.

Signing Lindor to a market-rate deal would likely consume a quarter or more of the Indians’ payroll. History has shown that allocating anywhere close to that much of your payroll to one player does not correlate to winning for any MLB team, not just small markets. As we saw with the signing of Edwin Encarnacion, any large payroll commitment by the Indians inevitably leads to cost-cutting down the line. It is reasonable to surmise that Michael Brantley would still be on the team if the Indians had not signed Encarnacion. At this point, Brantley would be more valuable.

If Lindor would take a short term deal, maybe 2-3 years with a club option tacked on, it might make sense for the Indians, even at 30-35 million a year. He’s that good. With a contract of that sort, even if the Indians decided to rebuild, they would find a robust market if they chose to trade Lindor because buyers would get cost certainty. Lindor might even go for that because he would still be able to enter free agency before he turns thirty.

But why should he? Bryce Harper, Anthony Rendon, and Nolan Arenado all got deals at least seven years long. None of them are clearly better than Lindor. Lindor knows he can get a deal that guarantees him more than $300 million, and he has every right to do so. The Indians can’t afford that.

Even if such a deal made sense on the field, some would have you believe it would wreck the bottom line. The way sports teams measure profitability is so Byzantine that they can make you believe whatever suits their argument. Teams that own their own broadcast rights can make that a separate company and stash the profits there. Did the Indians lose money when the payroll was pushing $140 million a couple of years ago? It depends on who is counting.

Here’s another way to look at it. The Dolans bought the team in 1999 for $320 million. If they had put that money into an index mutual fund (and been smart enough to sell at the peak two months ago), they would have $883 million today. At the time they bought the team, they paid the highest price ever paid for a major league team. As a general rule, that is an awful investment strategy; nevertheless, their initial investment has grown in value to more than $1.15 billion.

So, buying a baseball team, even one where the attendance is barely half what it was when they bought the team, has been a windfall for the Dolans. ould signing Lindor long-term increase the value of the team? Well, in 2014 Forbes magazine pegged the value of the Cavaliers at $515 million. A year later, the franchise was worth over $900 million. Was that a random jump, or did the Cavs sign a free agent who instantly made the team massively more valuable?

Dan Gilbert never worried about how much it cost to bring LeBron James back, because he knew it made his team more valuable. That’s not to say the Cavs’ way is better (although the trophy count says otherwise). And, while Lindor is one of the five best players in the game, LeBron is one of the five best players ever.

So, it’s not apples to apples. While it’s easy to blame the Dolans, the real fault lies with MLB itself for a financial structure where half the teams feel like a corner grocer competing against Walmart and Amazon. Fifty years after Curt Flood, these guys still act like there’s no better way to go about this. Meanwhile, the NFL, supposedly the most money-hungry, heartless sports league on Earth, has awarded four Super Bowl trophies to Green Bay, a city with barely a hundred thousand people. Can you picture Aaron Rodgers being traded because he makes too much money?